Why Jesus Loves Novels

Adam S. Miller reflects on childhood reading, Messianic fiction, and how a favorite sci-fi novel shaped his lifelong approach to faith and philosophy (presented at the 2017 Center Festival).

(My title, as noted, is “Why Jesus Loves Novels.” Let me confess at the start that I've never met Jesus, and I don't actually know that he loves novels, let alone reads them. But if he does read them, I suspect this is why he loves them.)

Do you remember the first real grown-up book you ever read from beginning to end?

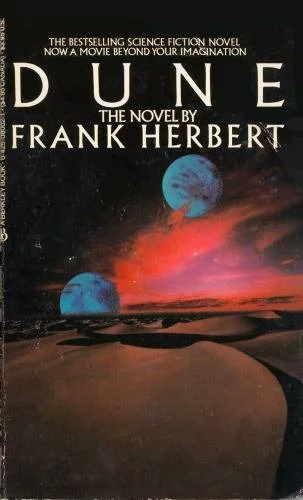

The first book that, unlike The Hardy Boys or The Three Investigators, was meant for adults? Do you remember how old you were? How heavy it was? Do you remember the cover? In sixth grade, I read my first two grown-up books at the same time. I read the Book of Mormon all the way through, and I read Frank Herbert's sci-fi classic, Dune, all the way through.

The Book of Mormon was bound in a stiff brown imitation leather as part of a triple combination, not pictured here. Though if you were lucky then you had one of those gold-covered paperbacks in your house.

Dune, on the other hand, was a fat, yellowed mass market paperback from my brother's collection of books, and the cover was printed in dark blues, browns, pinks, and blacks, dominated by swooping alien dunes of sand. When he handed over the book, my brother took pains to impress upon me that Dune was “the best science fiction novel ever written.”

I received it from his hands with reverence and I took up the hard work of reading it with devotion. I read both of those books for the first time at the same time. I've been reading the Book of Mormon ever since, but just last month I read Dune again for the first time in maybe 20 years. I'd forgotten a lot of details. Reading it again was harrowing, revelatory, and a bit embarrassing.

Re-reading Dune, I felt like my mind's veil, the veil that conceals from me the hidden inner logic of my own psychic economy, had been pulled back for a moment. And behind that magic curtain, Dune.

From the start, I've been keenly aware of how thoroughly the Book of Mormon has colonized my heart and mind, of how profoundly my life has been appropriated by it. But it really wasn't until a couple of weeks ago that I began to appreciate the size and depth of the emotional and cognitive crater that Dune had left in my 11-year-old mind.

Anyone who's read anything that I've written knows that there are only handful of ideas that interest me. There are only a handful of ideas about religion that have shaped all of my work in philosophy and theology, and I circle back to them again and again, and it turns out all of them are clearly and explicitly central to Dune. Dune, seems, is for me a kind of primal scene.

I don't think it's an exaggeration to say that without quite knowing it, I've spent the last 30 years thinking about Dune and trying to replicate Dune.

I suspect that I have essentially spent the last 30 years subterraneously treating Dune as a secret key to understanding my own religion. For better and worse, Dune and the Book of Mormon are hopelessly tangled up in my eleven-year-old mind.

Well, what is Dune? If you haven't read it, how would I describe it? Dune is, essence, a long, philosophically sophisticated meditation on what it means to be a messiah. Herbert intentionally designed the novel as a living, breathing, complex staging of what a real-world messiah would look like. And I'm not going to do an actual reading here, but let me just note three key ideas that are central to Herbert's staging.

One, Herbert sees the expansion of consciousness, especially the disciplined work of training and refining the raw human capacity for just plain paying attention, as the key to a messianic condition (in retrospect, it seems obvious to me that my own practical and theoretical interest in contemplative practices grew directly from my reading of Dune.)

Two, Herbert sees this messianic expansion of focus, attention, and consciousness as intertwined with family and genealogy. Messianic consciousness is, as he puts it, a race consciousness that wakes up to itself as the nexus of past and future genealogical threads that define the human race as such. Without realizing it I think Herbert's articulation of a genealogical consciousness has long been my template for understanding Joseph Smith's genealogical account of salvation.

And three, Herbert's approach to religion is profoundly pragmatic. He simultaneously treats religious forms and prophecies as intentionally cultivated fabrications and nonetheless as real and realizable.

On his account, the Messiah is both fiction and a reality. All the messianic prophecies have been, to some degree, cynically fabricated and propagated by the powers that be. But, and here's the thing, these prophecies still come true and overturn those same powers.

Perhaps I'll come back to these particular themes another time. But today I just want to use this personal discovery to reflect on the power of fiction itself. And in particular, I want to reflect on the theological power of fiction.

Yet this paper has a thesis. It's this: Theology, especially the academic kind, should be practiced as a form of fiction.

Or try this: academic theology, that is theology as scholarship, is best understood as a kind of science fiction that extrapolates from what is currently given in order to explore the full shape of the messianic powers that are only partially expressed at present.

Or to borrow a phrase from Marilyn Robinson, academic theology is like excellent hard science fiction writing in that both, “fling some ingenious mock sensorium out into the cosmos so that it can report back what it finds there”.

….

Keep watching– Watch Adam present his full essay on Youtube.

Keep reading– Find the full text of Adam’s essay in The Kimball Challenge at Fifty: Mormon Arts Center Essays

The Kimball Challenge at Fifty: Mormon Arts Center Essays

“The question will remain for people with religious natures: How can faith be integrated with culture? The desire to know God is so powerful that it seeks expression in every realm of life.”