Speaking over Silence: A Conversation with Susana Silva & Gonzalo Silva

A Guest post by Fleur Van Woerkom

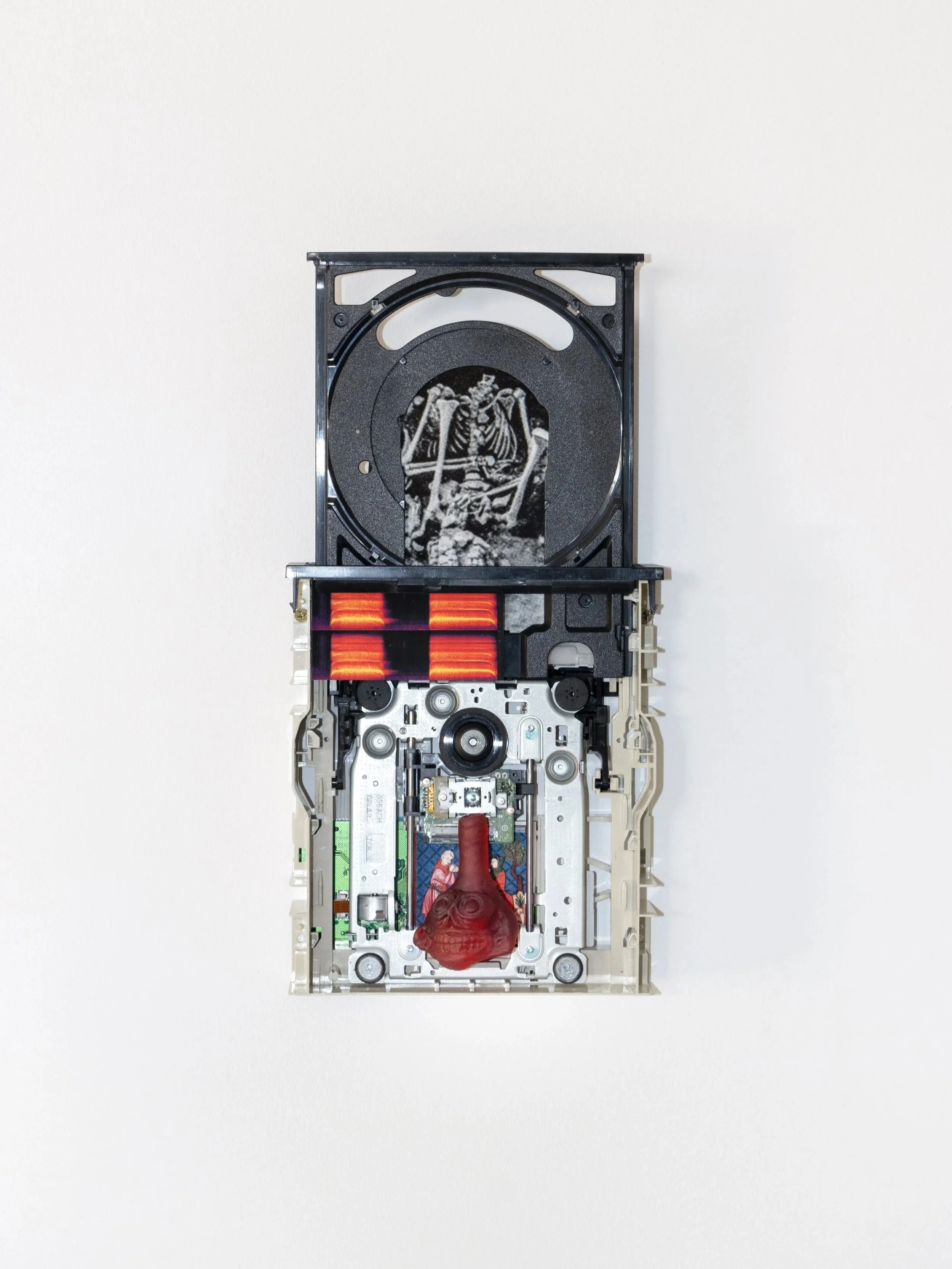

On August 5, 2025, Argentine artists and siblings Susana and Gonzalo Silva opened their first collaborative art show, Instrumentos de silencio, at Sargent’s’ Daughters, a gallery in lower Manhattan. Throughout the evening, visitors peered close to see the intricate details of Susana’s geometric paper cutting and Gonzalo’s photography and 3-D printed works, all of which explore themes of language, translation, technology, and the role of those modes in preserving the stories of communities across time and space in warm hues of red, silver, orange, black, and gold.

Instrumentos de silencio is a renovation of prior work which emerged as a meditation on Hilda Dianda, an Argentine musician who created the first electro-acoustic song made in Latin America by a woman. Susana and Gonzalo had worked together to create visual scoring, translating the music into Susana’s language of artwork on paper, exploring ideas of feminism, technology, and language.

Explaining their interest in language and technology, Gonzalo said, “Language is the way we go through the world. And it also constrains the way we see the world. Art, in that manner, makes new connections between already established things, so that way you can expand a little bit on the language you use to see and to talk about the world. Technological objects are a means to carry memory for a community, so if a community is depraved of technological objects, they are depraved of their memory. Even the metaphors we use have a historical value, a cultural value, a specific way of telling stories about the world.”

After winning the Ariel Bybee Endowment Prize in 2023 and knowing they would have a larger space to display their work, that original idea felt too constrained. Gonzalo said, “For the first project, Susana was going to be the artist, and I was going to be the curator and design all the technical aspects. But now that we have a whole exhibition and new ideas, we thought it would be okay to add my artwork in dialogue with hers, so we are using several materials to convey different perspectives on more issues.”

Family Mandates

Susana and Gonzalo were raised in a family that valued artistic practice. “We grew up in a house full of books. My mother loves Russian literature, and she is a beautiful reader. And my father too, he loved opera. Mother loved popular music, she loved Paul McCartney, but our father was more snobbish in his music taste. He wrote some books, and he liked to paint. He was an amazing photographer, just beautiful. He worked as a psychiatrist, but I don’t know why he was a psychiatrist. He loved so many things,” Susana recalled.

“It was a family mandate—to be a doctor, to be successful,” Gonzalo interjected. “Our mother, too, was a wonderful psychologist. She wanted to study art, but the dictatorship in the 70s came along, and her brother was in the Army, and he told her to avoid any artistic careers because of how it would be perceived from the dictatorship perspective. Lots of artists, communists, and just ordinary people disappeared during that time. So, my mother studied psychology instead of art. She had an unresolved desire for art.”

When Susana was 18 and Gonzalo was still very young, their father passed away. “I didn’t get to know him, but Susana and the rest of my siblings did,” Gonzalo said. Their father’s absence led to economic difficulty for the family. They moved a lot in the years that followed, and Susana had to stop studying to work, finding a job as a receptionist for a leather working business. Though her departure from focusing on art was brief and she soon returned to study graphic design, painting, sculpture, and art history, it marked a significant difference in the two siblings’ lives.

“Susana had to stop her training to work before resuming it, but I had the privilege to start as soon as I finished school,” said Gonzalo, who technically began by studying physics but quickly switched to art. Despite veering away from hard science, he is still deeply interested in the philosophy of science as it converses with art. In Argentina, art is taught with a mixed approach and an encyclopedic view, part theoretical and part practical. This duality makes for a very long process, but Gonzalo finished both his studies and thesis in seven years.

“It was hard—my father’s death really generated a mark in our lives. But we found our space, and Gonzalo grew up in a lovely home,” Susana says. Even today, pursuing an art career in Argentina is not an easy choice. For some, it means being hungry all your life. “Although,” Gonzalo mused, “that idea is not actually real. It’s a perceived idea about art—people think if you study art, you’ll be poor. But it is possible to have employment in the art area.” However, only artists with money can study whatever they want. “They are free. Really free,” Susanna said. Gonzalo agreed, “I don’t know how it is in the U.S., but in Buenos Aires, in Argentina, it is very common for the successful artists to come from more wealthy backgrounds, because you have to spend lots of money and time working on your art instead of working on other stuff.”

Scarce Resources

Time is a scarce resource that all artists must reckon with. “I lose a lot of time while I work,” Susana explained. “My work is visceral—I am visceral. I think in forms, in shapes, in explorations of clay and paper. I draw a lot of sketches that work and think together to then create other sketches. I have a very long process, which I must work on, because it is too long. My work is like a progression of exploration until I create it. I think with my hands to understand shapes and forms and space.”

Though Susana has worked with many mediums, her specialty is paper, which presents unique challenges. “Art paper in Argentina is expensive. I don’t have a job—I am a wife and mother, so my job is at home. I don’t have a specific payment for the tasks that I do, so I am very careful with how much I spend on paper supplies. But I think with my hands, and I figure out what I am making as I am making it, so it is a difficult balance. I love learning how other paper artists, whose art generates an enormous delight in me, solve these problems—how they communicate, how they suspend, develop, break, and compress the paper.”

After having her work displayed at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City a few years ago, Susana began experimenting with technology, designing her art digitally and then using a die-cutting machine to execute much of the tangible creation. This change in process has allowed her to explore more ideas and create more art without as much fear of wasted material. Perhaps connected to the introduction of die-cutting is Susana’s shift from organic shapes to geometric in Instrumentos de silencio, though the texture of each work likely has more to do with intention of emotional appeal than with the tools used to create it. “I’m not married to any process or style. I do what I need to put my idea in the space.”

Music, Memory, & Technology

See the collection from Instrumentos de silencio online.

“I explore questions like, how do we approach things like eternity? How do religions use technology to maintain contact with the eternal, with things way bigger than us?”

Technology, Science, and Spirituality

In contrast, Gonzalo almost always researches and plans his work in detail before creating it in physical form. “I like to research the topic and capture things that could be interesting in that area, just by my intuition, like images, phrases, and concepts. Then the first images emerge, and I work with them, and then there is a whole designing process. The design of the artwork and the research go side by side, and then I finish up the design and I use it with little to no modifications in creating the existing piece. I imagine the artwork before it exists, then I produce it, and that’s it. There are no changes. I get to decide great amounts of the artwork before it exists physically, so all the time spent designing the work digitally in turn reduces the time needed for the physical artwork.”

In addition to his attention to technology and science, Gonzalo is also very interested in spirituality. “I have a science fiction project about an artificial religion created to maintain some knowledge about nuclear waste depositories. In this world, there is a language problem because how do you manage to get signs that are readable ten thousand years in the future? We know that languages change very often and very much. One of the alternatives is to create a religion, or something that works as one, to have a priesthood of people that transmit this knowledge from generation to generation despite changes in language. I imagine the iconography of the artwork of this artificial religion through the centuries, and in this way, I explore questions like, how do we approach things like eternity? How do religions use technology to maintain contact with the eternal, with things way bigger than us?”

Paper as Religious Art

Susana also explores spirituality in her work, considering her vein of sacred art to be more illustrative. As a child, Susana sometimes went to church with her family, though there was a time when they stopped going. “When I was twelve, I started getting curious and read books from the church library, to understand what my grandmother and parents had experienced. I felt a need to explore all of it. I started attending church again, and never stopped.” As Susana continued reading church-published magazines and other materials, she soon noticed that almost all the visuals were coming either from Utah-based artists or from elsewhere in the United States. “It was impressive compared to any other religion I know, but it all came with a very unique aesthetic.”

“I never thought that the art I made with paper could work as religious art. But in 2017, the Church History Museum held a competition for artists. I thought, why not? I’ll try. I was without faith, without any faith at all, and at that time I was working with abstractions. I never thought my technique could reach the necessary level to be considered. It didn’t seem realistic to me, but I took elements from nature, and I made my art, and I won. I won the competition. That’s when I realized I could continue in that line of work and talk about the first axis of my life, my thoughts. . . of everything that I am. The change came in 2018. It’s funny, when I made that work, I got it photographed and then I put the real piece of paper art under my bed and stacked things on top of it. When I received the email saying they needed my piece in the United States to be shown, I wanted to die—it was completely torn up, so I had to redo it. I hadn’t had any hope that it would be considered! From then on, I’ve had the opportunity to talk about the most important things in my life through art.”

Creating a Window

Susana and Gonzalo wish to emphasize their gratitude for the work being done by the Center for Latter-day Saint Arts in bringing together artists around the world. “The vision they have is beautiful,” Susana said. “They are putting an eye in everything that Latter-day Saint artists are doing, which they sometimes do in silence, sometimes never being seen by anyone. There are so many places—Africa, Latin America, and other places that are full of members who are very good artists, without any opportunity to be seen. The Center is creating a window to let us show to the LDS world that people want to talk about gospel and God and find beautiful and creative ways to talk about the things they value.”

Though no longer showing at Sargent’s Daughters, Instrumentos de silencio will soon open in Berkeley, California at the Graduate Theological Union library on October 10, 2025.

About the Writer

Fleur Van Woerkom was born in California. She now walks and writes in New York.